How do black-box denoisers perform at the lower parameter-count regime, anyway?

So-called interpretably constructed deep neural networks often sell their methods by showing near state-of-the-art performance for only a fraction of the parameter count of black-box networks. However, can we consider these fair comparisons when the number of learned parameter counts are not matched?Background

In this post, we're talking about DeNoising neural networks – parameterized functions that take an image contaminated with random noise ex. AWGN,

and return an estimate of the underlying signal, . These DNNs are often trained by adding noise to a dataset of natural images, for example the Berkely Segmentation Dataset (BSD), and optimizing their parameters ("training") via stochastic gradient descent on the error (loss) between the estimated clean image and the ground truth, .

What makes a fair comparison?

In a broad sense, the "free variables" of these experiments are

training scheme

dataset

learning rate

network architecture (i.e. what operations are done inside )

functional form of layers (ex. )

hyper-parameters (num. layers, num. filters, etc.)

In the papers cited below, the same dataset (BSD432) is used to train each network. Training schemes may differ, but it is generally assumed that each team has done their best to maximize the performance of their network.

Novel functional forms are almost always the meat of an image denoising paper's proposed methods. The point is to demonstrate a "better" way of understanding denoising (via neural networks), or showing that a new tool can be used effectively.

A simple and convincing experiment to highlight this would be to ,

show the same/better performance to previously published methods using a less/equal number of "X",

where "X" is most commonly floating point operations (flops), unit of time, or learned parameters.

Flops and processing time are self explanatory benefits – and may not be equivalent due to parallelizability of the proposed method. Paying attention to learned parameter counts has some tangible benefits in terms of physically storing the neural network in memory, but it can also comment on the effectiveness of the proposed architecture in an Occam's Razor sense. Here, we equate a low learned parameter count to "simplicity", and look to methods with greater simplicity for insight. Beware that this connection is vague and should be put in context.

The Experiments

The our open access journal-paper where we propose the CDLNet architecture, we demonstrate a competitive[1] denoising performance to interpretably constructed neural networks, distinguished by faster processing time. We consider this a "fair comparison" as CDLNet is trained on the same dataset and has a roughly similar learned parameter count (~64k).

Ok, but state-of-the-art black-box DNNs (ex. DnCNN[2] ~ 550k) have hundreds of thousands of parameters. How do the interpretable networks perform in comparison? Worse. But it's obviously not a fair comparison. And they don't have to be fair comparisons if they're exploring the proposed method from a unique perspective[3] – in this case the black-box methods serve not as competition but as a benchmark. Nonetheless, some authors do cite these experiments as justification for the merit of their proposed method. Perhaps they're implicitly saying,

It's amazing we got this close, with this simple of a model!

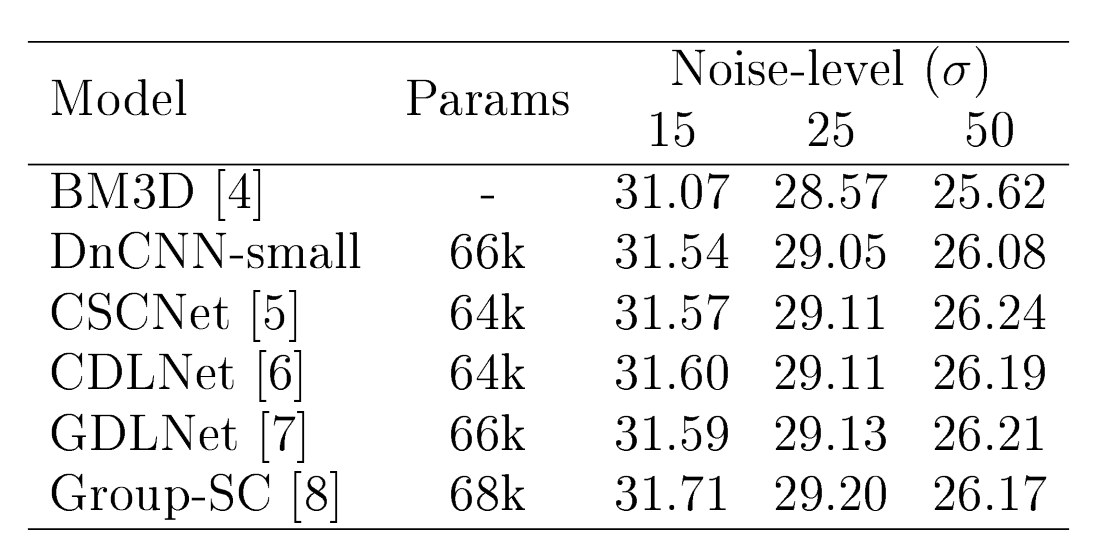

How close is close? To answer this, I shall fill in a missing piece of the puzzle: the performance of low learned parameter count black-box models. Specifically, the most popular black-box denosing network, DnCNN. Below is a table comparing the performance of small parameter-count networks (and unlearned BM3D[4]), CSCNet[5], CDLNet[6], GDLNet[7], Group-SC[8], and a small DnCNN model I trained using our CDLNet-OJSP PyTorch repository.

From the table, we see that DnCNN does perform worse than interpretably constructed denoisers (CSCNet, CDLNet, GDLNet, Group-SC) when at the low parameter count regime. This is in agreement with CDLNet outperforming DnCNN in the large parameter count regime, as shown in[6].

Appendix

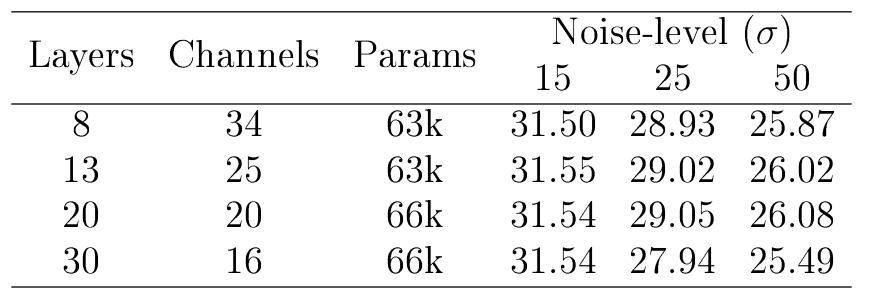

To get the numbers for the DnCNN-small model, I ran a small set of experiments varying the depth and with of the DnCNN architecture over the BSD68 test set[9]. The results of these experiments are presented in the table below.

| [1] | better than some (but not all), in some (but not all) cases. |

| [3] | novel methods are worth publishing even if they're not strictly "SOA". They may even lead to SOA methods if built upon further by other authors. |

| [2] | K. Zhang, W. Zuo, Y. Chen, D. Meng, and L. Zhang, “Beyond a gaussian denoiser: Residual learning of deep CNN for image denoising,” IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, vol. 26, no. 7, p. 3142–3155, 2017. |

| [4] | K. Dabov, A. Foi, V. Katkovnik, and K. Egiazarian, “Image denoising by sparse 3-D transform-domain collaborative filtering,” IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, vol. 16, no. 8, pp. 2080–2095, 2007. |

| [5] | D. Simon and M. Elad, “Rethinking the CSC model for natural images,” in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2019, pp. 2274– 2284. |

| [6] | N. Janjušević, A. Khalilian-Gourtani and Y. Wang, "CDLNet: Noise-Adaptive Convolutional Dictionary Learning Network for Blind Denoising and Demosaicing," in IEEE Open Journal of Signal Processing, vol. 3, pp. 196-211, 2022. |

| [7] | N. Janjušević, A. Khalilian-Gourtani and Y. Wang, "Gabor is Enough: Interpretable Deep Denoising with a Gabor Synthesis Dictionary Prior," 2022 IEEE 14th Image, Video, and Multidimensional Signal Processing Workshop (IVMSP), 2022. |

| [8] | B. Lecouat, J. Ponce, and J. Mairal, “Fully trainable and interpretable non-local sparse models for image restoration,” in European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2020. |

| [9] | I should've done this ablation study over a separate validation set, but hey, this is just a blog post. |